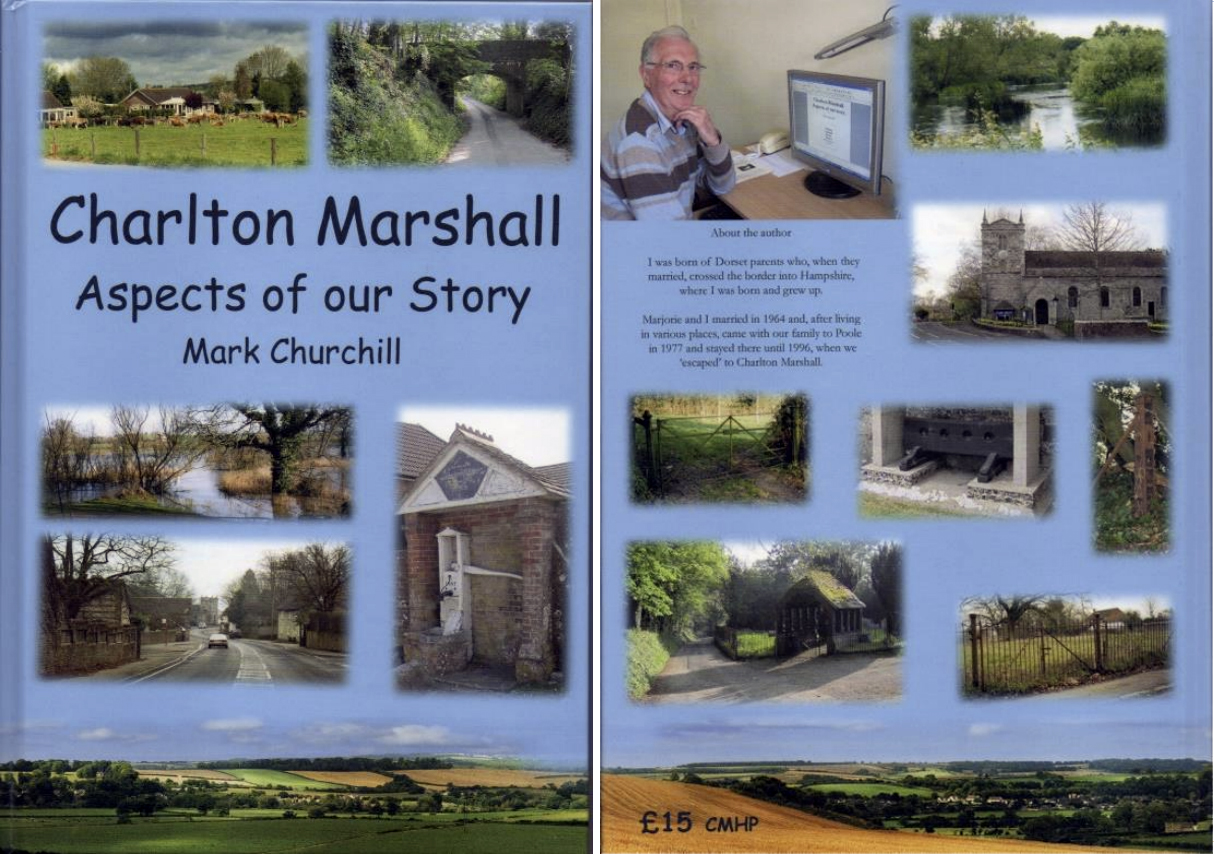

On August 22nd 2011, village resident Mark Churchill published ‘Charlton Marshall. Aspects of our Story’.

Lots of reminiscences, pictures and historical information came to light. Not all of it went into the book but none has been discarded and it will all be safely retained and deposited for use by future researchers or writers.

Mark is still collecting information as it comes to light, and if you have any pictures, documents or reminiscences about people or events up to about 1980, or parish magazines before 1991 to fill gaps in our set, please contact Mark by email: mk.cmanor@googlemail.com

When Mark and his wife came to the village in 1996, he started asking questions about all sorts of things and read anything he could find about the area. He eventually realised that the amount of information he had collected ought to be made available to other people, and the idea of the book was born.

By 2011, it was time to publish the book and when advertised it locally, the response was extremely gratifying and far greater than anticipated; all 400 copies that were printed had sold out within 3 months. It has not been practicable to do a reprint but copies are available in Dorset Libraries and at the Dorset History Centre.

The publication was intended to be not-for-profit but the great response and quick sale of all the books meant that a worthwhile amount of funds could be distributed to various local organisations and other charities.

This is the gist of the talk I gave on the Book Launch Evening 25.08.2011. Thanks to all who’ve helped with tonight and to all who’ve helped with this project in any way, and most of all to Marjorie, without whose patience and attention to detail, it would not be as good as it is.

Sometimes people wonder how this project came to be. So do I! We came here from Poole in Aug 1996 – just 15 years ago. I probably started asking questions about the village and its past fairly soon, because I’m like that; anywhere that we’ve ever lived, or anywhere that we go on holiday – I have to find out something about the background. I’m not sure whether I set out intending to write a book or not, but by 2004 when the Parish Plan was launched I had decided there would be a book and I had coined the name The Charlton Marshall History Project; I remember thinking that if I included the word ‘village’ that excluded the more distant areas of the parish, and if I included the word ‘parish’ people might think it was restricted to the church, because lots of us don’t realise there are two parishes – the C of E parish and the political one – although in our case as in many others the boundaries are the same.

One of the things that gave me an incentive quite early on was Gilbert Bennett’s memoir of the village, written I guess in the 1950s or early 60s; there were still a few copies on sale in this room at the time, it really is great – being written by someone who had lived here from 1904 and was very much involved in the life of the village at many levels. I hope some copies might be printed again some time.

Material has come from many sources as you will have realised. At one period I followed up quite a few names from the church visitors’ book – former Clayesmore pupils and former residents or their descendants come for visits, often looking for family history. More recently the village website has also been a good source of contacts. Earlier this year a lady from Kentucky made contact to say that she’d come across some snapshots that her father had taken when he was stationed here during the war; would I like to see them? Would I?? Two of them are in the book.

I suppose really there are 3 main types of material:-

- People’s reminiscences which can be fascinating, difficult to record, and sometimes contradicted by other people’s. I was aware of the ideal of oral history – high quality recording and permanent retention of the spoken word (especially important where local accent/dialect was involved) but I decided that I had neither the skill, the equipment nor the time to do that. I used a small Dictaphone type recorder, played it back at home and typed it out – very time consuming in itself and sometimes extremely difficult due to the voice or accent of the person I had interviewed, but very worthwhile; the recording was then deleted and the typed version retained.

- Original material such as property deeds, minute books, marriage settlements, photographs, monuments, gravestones, account books. Local people kindly loaned me material, and much more was found elsewhere, mainly in the Dorset History Centre (the Record Office).

- Secondary material such as books, newspaper reports and magazine articles. These are extremely useful but accuracy cannot always be guaranteed. I had two main sources for newspapers; some years ago, The Times newspaper was digitized and available on the internet for a few weeks on a trial basis and I also found that Poole Local History Centre had 19th century copies of The Blandford Express and The Blandford Weekly News on microfilm; for over 2 years I was working part time about 5 minutes walk away and was able to arrange my days so that I had long lunch hours which I spent squinting at microfilm.

The book that eventually emerged is not the one I originally wanted to produce – hopefully it’s a lot better. So how did we get to ‘Charlton Marshall. Aspects of our Story.’? I think that was always my chosen title, cautious and all-embracing. I knew that I’d never have all the loose ends tied up but I wanted the story to be as complete as possible. Anyway, there came a point when I thought ‘If I don’t soon stop researching and begin writing, I’ll never produce anything. There’s enough material now to produce something worthwhile; I really must start writing next year.’ That was 2007 and halfway through 2008 I hadn’t started so I said ‘Definitely next year.’ Which would be 2009; so on New Year’s Day 2009 I sat down and typed a paragraph to make sure I got started; according to the computer record it was 29 minutes past six that evening! And the rest, as they say, is history.

I knew the first version had to be shortened and sharpened so I set a target of at least 25% reduction. In fact I achieved only about 10% and then it grew again for various reasons and is now over 80,000 words.

In September 2009 a lady in her 80s, who used to live in Spetisbury, came back on a visit; she said she had a lot of old parish magazines and would they be of interest to anyone; fortunately she was speaking to someone who was ‘on the ball’ and they were sent down when she got back home. I found that they covered the 1930s and 1940s – a significant time for which I had very little information, so I stopped writing for several weeks and worked through them.

So how did I come to publish this myself? I always wanted to produce something for the village at a price that people would be happy to pay – especially those who don’t normally buy books – and I thought I was not likely to do that if I had to go to a publisher – even supposing I could find one who was interested. Also, being me, I wanted control of what I produced. I looked into the possibilities of self-publishing (often called Vanity Publishing – maybe for obvious reasons) and I didn’t like a lot of what I found. Then Marjorie found a book reviewed in the Blackmore Vale that she wanted to buy and it was published by Brimstone Press at Shaftesbury; we’d never heard of them, and nor had many other people either, but when I looked at their website they described themselves as having ‘a co-operative approach to self-publishing’. For various reasons I decided not to use them but what I did get from them was the recommendation of the printer that I’ve used. After working out various things on the printer’s website I came up with a list of questions and arranged to meet their Sales Manager in Chippenham; he gave me lots of useful advice and information and a quote that made sense because I was planning to do all the typesetting and picture layout myself – foolish person!

I still didn’t know how I was going to produce the text and pictures for the printer. I eventually decided to use Open Office software – like they have on the computers here in the Church Room. After a while, I found it didn’t really seem stable enough for a document of my size, but I had got so far that I was unwilling to start again and decided to persevere with it; it has had its moments, not least when it seemed to move graphics and text around of its own accord, but that may well be due to my own failure to understand sufficiently how it works.

As recently as spring this year, when anybody asked me about the book, I would say ‘Oh that’s a long way down the line yet.’ And all of a sudden, one day, it hit me that it wasn’t really very far down the line at all; I knew exactly how much material I had, most of it was already typed and pictures pasted in, and I knew exactly how many pages I had still to go. I reasoned that if I didn’t stop for a while and plan the publishing, I’d have a long space of wasted time when the book was finished but I couldn’t print it because I had no idea how much interest there would be and therefore how many to print. So I took stock and came up with August 22nd as a viable publication date, and it was then no longer a distant vision but a concrete reality with a live date that I had to meet, and while that is an excellent thing to have, it meant that I had now moved from a leisurely, if time-consuming, hobby, to a business commitment where I couldn’t let people down – and that gave it a very different feel.

There were a few scary moments in the last couple of months. I had sent small test files to the printer months ago and they were fine but just needed me to change the colour definitions; that didn’t sound like a problem, and so I just put it aside until – you’ve guessed – a couple of months ago. For the main text and ‘black and white’ pictures the file was required as ‘100% grey’; I could find nowhere to deal with that. The person I was now dealing with at the printer suggested I sent him a full file and he’d run it and send me the output. When it came back some of the pictures looked awful – just like bad photocopies; then I discovered that although all my pictures looked like ‘blacka dn white’ and I had used Photoshop software to remove the colour, some were still recorded as RGB (which stands for Red Green Blue i.e. colour) whereas some others were recorded as Greyscale; so I made them all Greyscale and reloaded them into the text – a hairy operation as it had the potential to disrupt all sorts of things! That went OK and when I got a new set of proofs back the pictures looked much more consistent and as I was going through them, I noticed something I’d not seen before – I could have changed them to Greyscale in the text without reloading them. Such is life! There have been a few other scary moments. Marjorie noticed a missing word and I found that I had somehow accidentally deleted every occurrence of the word ‘large’; fortunately I still had an early enough version on file to do a search and put them all back! Marjorie and I have both read the text and the captions so many times and made corrections and improvements, but there came a time when I knew I had to take the plunge – stop checking, create a final version, pay the money, send it off, and trust. If I didn’t, I was in danger of missing August 22nd although I’d allowed plenty of time initially. The morning after I did that we were eating breakfast and I remembered an amendment I’d forgotten to make! Fortunately not an important one.

We had delivered leaflets for the pre-publication offer to Charlton, Spetisbury, and parts of Blandford St Mary. Several people helped us but Marjorie and I did the lion’s share and by the time Marjorie got back home on the Friday afternoon, the first two people had brought their forms back, and from then on over that weekend there was a steady trickle of people through our front gate; then the postal ones came steadily too. You may remember that I said I needed about 200 pre-publication orders; I got an amazing 320+. I had kept a list of contacts – mostly by email – anyone who had shown the remotest interest over about 5 years and that brought in quite a few but of course most were local. Some of you rustled up orders from your families and previous residents – thank you very much. The largest single order was for 8 although another family comes to 11, I think, if you count them all up. The most distant are Australia and New Zealand. So, there we are. Would I do it again? Possibly, but not for a while, and I’d try to make sure next time that I knew what I was doing.

Mark Churchill.

The Stour valley was occupied from prehistoric times. At the top of Church Lane, and especially in the fields around Gorcombe and Charisworth, there are lots of small tumuli and burial barrows from thousands of years ago. Look too at Hod Hill, Hambledon Hill, Spetisbury Rings or, across the valley, Buzbury Rings.

Bronze Age remains (2000-4000 years ago) have been found off Church Lane which itself continues across the ford behind the church and on up the hill to pass close to Buzbury Rings. It is quite possible therefore that the first settlement, that eventually led to the present village, was around the river crossing.

The Romans came to the area early in the first century A D and were around for about 400 years. Remains have been found near Charlton Barrow and there is the villa further north at Shillingstone and another to the east between Tarrant Rushton and Witchampton.

The ancient yew tree behind the church suggests that Christians, at an early date, took over a pagan worship site. The location of the church near the river also suggests that it was probably a place for Christian worship at an early date when converts were still being baptized by immersion.

In 1086, in the Domesday Book, Charlton is linked with Pimperne and is held by the king himself. It was only another hundred years or so before the village was in the hands of William Marshal.

‘Charlton’ means farmstead (or settlement) of the free peasants and is quite a common village name in England. It is made up of two Old English words, ceorle (free peasant) and tun (settlement) which later became our word ‘town’.

‘Marshall’ was added in the 13th century when the manorial lands here were owned by the Marshalls who were Earls of Pembroke. They also owned Sturminster Marshall. William Marshal (sic) (1147-1219), Earl of Pembroke, described by one writer as ‘the David Beckham of his day’, was recently the subject of a very interesting BBC2 programme “The Greatest Knight”.

William was the younger son of a minor nobleman; as such he had no inheritance of land but through his bravery and skill he became one of the most powerful men in England (possibly in Europe). At the age of 43 his marriage to 17 year old Isabel de Clare brought him considerable land and wealth, and subsequently the Earldom of Pembroke. I do not know how or when he acquired his lands in Dorset; probably they were already held by the Earldom of Pembroke.

William was one of the signatories of Magna Carta in 1215 and after the death of King John the following year, he became, at age 70, Regent for the 9 year old King Henry III. During his time as Regent, Magna Carta was re-issued under his seal.

William’s effigy is behind the throne in the House of Lords and he is buried in the Temple Church in London where his grave can still be seen.

Marshal was originally a job title, keeper of the horses, which developed into head of household security, but from William’s time onwards it became a family name.

I have spent quite a lot of time working through the Churchwardens account books from the 17 th and 18 th centuries. I thought a few extracts might raise a smile and also remind us how very different life was then. I have left spelling unchanged but have interpreted where I think it might be necessary. The first selection is of payments made to travellers passing through the parish.

1657 To John Barnes that came out of Turkie

1657 To 2 poore women

1657 To 2 poore soldiers which was wounded in the kings servis

1663 Janu 18 th Paid a destitute man and his family being cast away att St tiues in Cornwall

Febru 28 th Paid 4 poore seamen being cast away against Cornwall having a pass to goe to Porchmoth and so home

Many payments were made to villagers for killing animals that were harmful to an agricultural community.

1657 To widow Coles for hedgs (hedgehogs)

1657 To William Merrit … for 2 pole cats

1676 For Shooting the Rookes

1676 For fower dousen of Sparrows

1711 John Morgin for a otters head

There were also payments for the church services and building.

1663 Paid for 3 quarts of wine and half a pinte against Ester and 2 penneth of bread,

1663 Paid the widdo ball for waishing the surples against Easter (washing the surplice for Easter Day)

1657 For 10 bushells of lime

1657 To the massons for mending the church wals

1657 To Robert Harden for glass for the church window

1657 To Henry Jenkins for mending the bells

Our church is certainly our oldest building. Until I read one of the old guide booklets I hadn’t noticed the distinct difference between the stonework of the mediaeval tower and the rest of the building which was remodelled in 1713.

The church is very light inside because it has no old stained glass. All the side windows are clear glass from 1713. The stained glass in the windows at the east and west ends is twentieth century and the windows commemorate members of the Walker family. Samuel Arthur Walker was Rector from 1886 to 1904. When he retired he bought Charlton Manor and the family played a pivotal role in the village for the rest of the century.

The church is included in Simon Jenkins’ book “ England’s Thousand Best Churches”. Along with the town centre church in Blandford it is reckoned to be one of the best examples of a Georgian Church outside London. It is of course actually from the reign of Queen Anne, and is often referred to as ‘Early English’ in style. Jenkins says ‘interior in style of Wren’. However The Georgian Group was pleased to visit in 1962.

Our church and Blandford’s have certain similarities of style and it is often thought that our 1713 remodelling was done by Thomas Bastard, father of John and William Bastard who were responsible for the rebuilding of much of Blandford after the fire of 1731.

Much of our church is just as it was in 1713 but some fairly extensive restoration work was done in 1895 and at that time the box pews were removed and were remade into the pews that are in the church today. If you want to see pews that are probably fairly similar to the ones we used to have, you should go to the little church in the farmyard at Winterborne Tomsom or the one at Chalbury just off the Wimborne to Cranborne road; both of those churches are of course well worth a visit in their own right.

Another interesting feature of our church is the memorials on the walls; other research that I am doing is bringing some of them very much to life and at some future date I shall hope to write brief articles about some of the people commemorated there.

Who was John Truelove of Charlton Marshall? This John Truelove was Gentleman, Churchwarden, Surgeon, Widower, Debtor. Each of those words tells us something about him but his name is known because in 1742 he took his own life, apparently after a series of misfortunes.

John (also known as James) had retired from London to Charlton Marshall. To retire from the city to the countryside is not a new idea! In the mid 18th century though, the countryside was very different from what it is today. Roads were unpaved, most dwellings and land were leased from the lord of the manor, and tithes were paid to the clergy. The poor travelled on foot and seldom went further than the nearest market town, in our case Blandford, while the better-off went on horseback or by horse drawn conveyance.

At the time, Charlton Marshall consisted of the cottages in Gravel Lane, and others in The Close and River Lane, and around the centre of the village. There were some farms including the outlying ones that still exist today and two or three bigger houses, one of which John Truelove rented from Andrew Hopegood, the lord of the manor.

John was well respected in the village. He was married to Mary and had several children but at least one of them, named Mary like her mother, died in infancy and was buried at our church on October 14th 1735. She is described as ‘infant daughter of James and the late Mary’ so it is likely that her mother died in childbirth or soon after, meaning that John and his other children had suffered a double tragedy. It appears too that they may have only recently moved into the house opposite the church on the site of what is now Charlton House Court. The very next year however, John became churchwarden with Henry Horlock whose monument is on the south wall of the church near the pulpit.

John got into debt; we do not know how, but by 1742 things were really playing on his mind. He thought he could see a way out; his late wife had had money of her own which had been put in trust for the children – could he find a way of accessing it? No, and this probably pushed him further into both debt and despair. The final straw came when John Thorn, a mercer from Blandford, sued him for payment of money owed to him; had he been buying expensive fabrics from the mercer or was it just one of a pile of smaller unpaid accounts that had built up?

Two days before the case was due to be heard, Thorn offered a way out – ‘give me everything you own, go abroad, let me sell your goods and take what you owe me, then I’ll send the balance on to you’. This idea didn’t appeal, so instead, Truelove paid off his servants, sent his children away, gathered a good supply of furze and locked himself indoors. When the officers of the law arrived on the morning of 20th October 1742, he set the place on fire and shot himself. The house was completely destroyed but thanks to it being a calm day no other buildings were damaged.

John Hutchins the 18th century Dorset historian wrote ‘Nothing remained of this unfortunate man, but some of his bowels, part of his backbone, and one of his feet in a shoe’.

Mark Churchill.

1789: The Newfoundland Connection

Two families in Charlton Marshall are known to have had connections with Newfoundland.

The Whites, a prominent Quaker family, were merchants and traders in Poole. Samuel White built Charlton House in about 1810 and shared the title of Lord of the Manor of Charlton Marshall with Thomas Horlock Bastard the elder. In his will Samuel left 1/- per week for the Sunday school which was run for the education of the children of the poor of the parish. His nephew Samuel White who owned the house after him, gave to the Rector and Church Wardens in 1847, land for a school, and what we know today as the Church Room was built on it. It was used as a school for about 50 years until educational needs changed and has served many useful purposes since.

The Streets were a local family who first appear in the records in 1717. They were manual workers and craftsmen and were often employed to repair the church clock or the gates. In 1768 William Street is described in a property deed as a wheelwright. William was one of six recorded children of Mark and Mary. The youngest was Thomas who went to sea and eventually became one of the White’s agents in Newfoundland – a very responsible position. Thomas benefited hugely from his relationship with the Whites and in 1789 set up his own firm Thomas White and Sons. At the same time he settled in Poole with his family, leaving the sons to deal with the Newfoundland end of the business. Thomas bought property in Charlton Marshall including a house; I’d dearly love to know where that was, so if anybody has copies of old deeds please see if the names Street or Clark, or the property known as Hurdles, features anywhere in them. Thomas died in 1805 and his widow Christian lived in the house until her death in 1816. There is a plaque on the north wall of the church recording Thomas and Christian. The Street family graves are the two grade 2 listed table tombs on the right of the church path, together with a slab and a headstone beside them.

Major General Sir Charles Walters D’Oyly, 1822-1900, Creator of Newlands, Charlton Marshall.

Sir Charles, as I think he was usually referred to in the village, came to Charlton Marshall in 1880 after a military career in India. He and his second wife, Lady Elinor, took a significant part in village and district life as would have been expected of people of their status.

Sir Charles was ninth baronet of Shottisham, Norfolk, having succeeded to the title in 1869 on his father’s death, and was himself succeeded by his half-brother Sir Warren Hastings D’Oyly in 1900.

Sir Charles was born in India in 1822. His father and uncle were both senior civil servants of the East India Company. He and his younger brother George were sent home to Sherborne School where, I am told, his name can still be seen boldly carved into the lid of one of the old desks which have been incorporated into windowsills. His address in the Sherborne Register is given as Steepleton House Blandford (the estate on Steepleton Bends north of Stourpaine) which the family were leasing at the time from the Pitt Rivers family. From Sherborne he went to the East India Company’s Military Seminary at Addiscombe in Surrey and his military career began in India the day before his 20th birthday in December 1842.

In India on 25th September 1855, Charles married Emily Jane Nott and the following July their daughter Mary Lushington D’Oyly was born. Charles was in charge of a Government Stud Depot at Haupper near Meerut; this comprised some 1800 young horses being bred for army use. In 1857 the Indian Mutiny broke out and Charles and his little family, together with other Europeans, were forced to make an overnight escape from their home. Emily, who was pregnant, went into premature labour and a stillborn son was delivered; sadly Emily also died and mother and son were buried together. Leaving little Mary with another family, Charles made his way back in an unsuccessful effort to save the stud.

A summary of Charles’s military career is found on a large brass on the north wall of the church in Charlton Marshall. Research by the late Captain Tim Ash has noted one or two discrepancies in the detail. Charles married his second wife, Elinor Scott, in 1867; there were no children from this marriage. They returned to England in 1872 and lived at Steepleton House. Sir Charles retired from military service two years later and by 1880 they had bought a ten acre plot in Charlton Marshall and built Newlands on a part of it that had been known as ‘Sunny’.

Sir Charles, and his uncle of the same name, were both accomplished amateur artists and their paintings still appear from time to time in specialist auctions. An internet search on the name brings up quite a selection. There are Indian scenes, rural scenes around Charlton Marshall, and humorous sketches of Indian and military life, among others. I was told by a lady who worked at Newlands that an attic room with roof lights had been a studio.

In 1881 the household included a cook, parlour maid, house maid, kitchen maid, coachman and groom and I was told that in the 1930s there was still ‘a full staff’. The appendage ‘Manor’ was added to the name ‘Newlands’ in the latter part of the 20th century and recently it has been renamed again as ‘Newlands Manor House’.

In common with Thomas and Sarah Horlock Bastard of Charlton Manor, and Henry and Augusta Huntley of Charlton House, Sir Charles and Lady Elinor hosted teas for village children, provided coal to the poor in harsh weather, responded to appeals of various kinds, and were active in church life. They gave newspapers and magazines when the schoolroom was opened in the evenings as a reading room and Lady Elinor held Mothers Meetings at Newlands. For a while Sir Charles was Chairman of the Blandford Cottage Hospital Committee of Management and his wife is often mentioned for gifts to the hospital such as fruit, flowers, vegetables, ‘old linen’, toys and a bath chair.

Sir Charles supported many organisations in Blandford including the Literary Institution, the St John Ambulance, and the Constitutional Club. He also sat regularly as a magistrate at the Blandford Court of Petty Sessions and it is interesting to see in the reports of its proceedings the names of residents of Charlton Marshall who appeared before him from time to time. Inevitably when the Blandford Literary Institution started an art class he was involved in it and in 1894 he supervised the arrangements for a Grand Indian Bazaar put on by the Constitutional Club; Lady Elinor was one of the stallholders.

It is no surprise that when Charlton Marshall’s first Parish Council was formed in 1894, Sir Charles was unanimously elected its Chairman and probably few, if any, are aware that the iron gates inside the church porch were given by Lady Elinor after the restoration work of 1895.

The following is taken from the tribute to Sir Charles in the parish magazine in August 1900 by the curate Rev John Cattle. By the death of Sir Charles D’Oyly, which occurred after a long illness at Newlands on the evening of July 11th, the parishioners of Charlton, and many others will feel that one of the best of men has been taken away. His circle of friends was so large, his sympathies so widespread, and his sphere of activity and usefulness so extensive that the number of notices of his death which have appeared is not surprising. But his memory claims our respect and esteem, especially as a resident in Charlton, where for many years he has spared no pains and no expense in any way that he thought calculated to promote the welfare of his adopted Parish I have always found (him) to be an ever ready and generous, ever sympathetic and unassuming helper his affable unfailing courtesy, conciliatory address and sound and respected judgement were invaluable factors in securing co-operation “Do nothing that is evil” was his family motto, but he took a higher standard in life

his habitual practise (sic) to do everything that was good.

Lady Elinor continued to live at Newlands until her death in 1914 and she is buried with Sir Charles just inside the entrance of the old cemetery in Charlton Marshall.

In September 1891, at a concert in the Reading Room (Club House) Sir Charles told a story from his time in India. It was entitled ‘One for his Nob’.

In the hot season in the North-west Provinces of India, when Sir Charles as a mere Captain in the army had just returned from home leave in England, he was in charge of a Government Stud Depot comprising some 1,800 young horses that were being bred for army use. Large quantities of hay and straw were grown across the area and stored at the site. He was returning from the stables one day when he was approached by an Indian man who wanted to talk privately with him.

On being assured that there was no-one within a quarter of a mile, he said that a gang of robbers was regularly stealing hay and straw at night from one of the rick-yards. When asked why he had not given this information before, he said he had done so, but that Sir Charles’s predecessor had called him a liar just hoping for a reward.

Sir Charles was obviously a little more canny than his predecessor, for although, as he said, he was initially inclined to share his predecessor’s opinion, on reflection he thought ‘what can be the object of this man telling me a falsehood which can be so easily proved or disproved?’. So he called the man’s bluff and offered him fifty rupees if it was proved true, or a beating if it was proved false. The man accepted the offer without hesitation, and they arranged to meet at 10.30 pm that night under a particular tree near the store.

So they parted, and in order to have some support on the exploit, Sir Charles invited the depot veterinary surgeon to dinner, who, when told of the exploit, readily agreed to accompany him. They set out in the dark after dinner and found their informer at the pre-arranged spot, but there was no sound of any activity in spite of the fact that it was a still night. The informer assured them that the robbers were already at work; they put their ears closer to the ground and could hear the sound of voices and movement in the rick-yard nearby.

They crept up, went around the ditch, that had been created on the inside of the yard when the mud for the wall was dug out. They surprised a man carrying away a load of straw on his back; he dropped it, Sir Charles fell over it in the dark, pulled out his revolver, and fired in the direction in which the man had fled. Hearing a thud, he feared he had killed him, but all was well, he had only fallen to the ground in fright so was taken prisoner.

Sir Charles then caught sight of someone else slinking away in the darkness; so left the first man with his companion and gave chase. When he caught up with him, the man tried to evade capture and was given a hefty whack on the head with a bamboo truncheon, which stunned him for a moment. When a lantern was shone on him, it turned out to be their original informant, presumably having second thoughts about what he had done and hoping to escape unidentified, fearing retribution from his own people.

They took him back with them and got him patched up by the doctor and gave him double the promised sum as some sort of compensation for injury.

The robber who had been caught was also taken back and eventually persuaded to disclose the identities of his accomplices; when the head clerk went to the village to apprehend them, he found a large store of stolen forage. Five men were arrested and later tried, found guilty, and sentenced to terms of imprisonment ranging from six months to two years.

Sir Charles finished his story by saying ‘Thus ended our nocturnal police adventure, for our management of which, I received a handsome letter of acknowledgement from our Departmental Chief, for having discovered and broken up this organised system of wholesale robbery’. Mark Churchill.

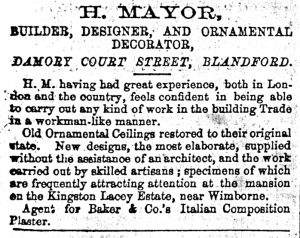

Henry and his brothers followed their father to work as plasterers at Kingston Lacy and their work can still be seen in some of the decorative ceilings there today.

In 1862 Henry married a local girl, Elizabeth Palmer, but sadly she died just over 10 years later leaving him with four young children. By that time they were living in Damory Court Street in Blandford and Henry, as a Master Plasterer, had his own business; in 1871 he was employing seven men and was engaged in all forms of building work. He was responsible in 1877 for the chapel in Alexandra Street where the Evangelical Church now meet.

Henry continued his links with Charlton Marshall through the chapel in Gravel Lane where he led a Bible class for adults and was secretary of the Temperance Society whose meetings there and in other venues around the area were extremely well attended.

His consuming passion however, and one that would eventually lead to his downfall, was the rights of the working classes. He was heavily involved with the National Agricultural Labourers Union (NALU) and eventually took on the role of its Dorset Secretary; this proved too much in addition to running his own business and in 1879 he was declared bankrupt, his home and all his assets sold to cover debts. Homeless and destitute, he went to live with his sister-in-law at Milford near Salisbury where he died in 1884 aged only 58.

NALU had been founded in 1872 by Joseph Arch, a Methodist local preacher, and within two years had achieved a membership of 86,000. He spoke at rallies in Blandford on several occasions – sometimes outdoors in The Tabernacle or Market Place. One aspect of the Union’s work was to help labourers find employment – sometimes in other parts of the country and increasingly in the Colonies; Henry Mayor was deeply involved in this from the beginning. Later the Union would also campaign for electoral rights for the working classes. The Union was dissolved in 1896 and in 1906 a new Union was formed which later became the National Union of Agricultural and Allied Workers.

For more details of Henry Mayor and NALU see ‘Henry Mayor’ a booklet published by Blandford Museum in 2016.

1847: Church Room

The building was originally a National School; the land was given in 1847 by Samuel White of Charlton House, which stood where Charlton House Court is now located.

Samuel was a Quaker and his concern for the education and welfare of children must have overcome any religious concerns he may have had as he vested the plot in the Rector and Churchwardens, and National Schools were a strictly Church of England affair.

This was a time when education was almost exclusively the prerogative of the wealthy but concerns were growing that all children should have access to at least the basics of “reading, writing and ‘rithmetic” and charitable societies were being founded for that purpose.

The building was financed by public subscription and from the outset was frequently used outside school hours for entertainments, meetings, tea parties etc… In December 1894 the Curate, the Rev JW Cattle opened it two evenings a week as a reading and games room and it seems to have been well supported. The following year it was open three nights from 7.00 to 9.30 pm. By 1897 it was open four nights from 6.30 to 10.00 pm with Sir Charles and Lady D’Oyly of Newlands supplying newspapers, magazines, etc.. In that year £30 worth of repairs were carried out; I have no detail of the work done on the building itself but they lined the back wall with glass – presumably to prevent people climbing over it.

Renovations were again being carried out in 1906. A stage was built which must have been very cosy!

By 1909 it appears to have ceased to be used for the school as the current Curate, the Rev FS Beale wanted it enlarged to become a Parish Room. It is obvious that the room was never extended although the kitchen/ toilet area may be later than the rest of the building (does anybody know?) In 1910 a new wooden floor and a new stove for heating were installed; concerts and flower shows and other fundraising took place; the estimate for the floor was £19. 10s 0d. In November the Parish Magazine records ‘The earth outside part of one of the walls was higher than the floor level … This earth has been removed and the excavation filled in with concrete’.

In 1913 there was talk of ‘much needed repairs’; when they were completed it was reported ‘our schoolroom now possesses a comfortable and cheerful appearance’.

The area in front of the building was the school playground bounded by railings which remained in place until damaged beyond repair in 1941 by a lorry; they were donated to the scrap metal drive for the war effort.

The original entrance was through the doorway that has recently been removed to make way for the new toilet block. The present entrance was created from the second window in the front wall.

The building continued in use as a school until the last years of the 19th century when the various Education Acts introduced universal free education by the state.

The name ‘Church Room and Village Centre’ dates from the early 1990s after considerable work was done to make the building more usable and to accommodate a Post Office counter after the one in the village shop was closed. The board outside proudly proclaims ‘Church Room and Village Centre’; long may it continue.

From the Blandford Express August 12th 1871. A report of a case in the County Court.

F Shave v W Goldie of Charlton Marshall. Claim £2. 5s. value of a crop in a cottage garden and piece of allotment – 30 lugs at 1s. 6d. Plaintiff had been serving as shepherd for the defendant, and on being dismissed requested payment for the crops as above. Defendant thought the charge too high and would only consent to pay for seed and labour which he considered fair. The Judge however, thought that the claim by the poor man was only just and fair, consequently he gave judgement for the amount to be paid forthwith. Defendant: then I shall charge him rent. The Judge: then if you come before me you might be well assured you won’t get it.

(A lug was a box or basket that held between 28 and 40 lbs of fruit or vegetables.)

1877: Primitive Methodist Preaching Room

From the Blandford Express July 7th 1877.

‘Charlton Marshall. Primitive Methodist Preaching Room. The opening of this room took place last Thursday evening by a public tea and platform meeting, which were satisfactorily attended. Mr W Hunt who had purchased the cottages – two of which form the said room – took the chair. Suitable addresses were delivered by the Rev J Leach, Messrs Lush, Joyce, &c.’

This preaching room was in The Close above the Church Room. It remained as a Methodist chapel until the congregation transferred to the chapel in Gravel Lane around the turn of the 19th / 20th century. The Gravel Lane chapel eventually closed in 1951.

1880: Fellmongers

Question 1. What is a fellmonger?

Question 2. Did you know we used to have one in Charlton Marshall

When I first came across this term in the 1880 edition of Kelly’s Directory my mind went to ‘fells’ as in ‘moors’ or ‘hills’, but that didn’t seem to make much sense, so I consulted the dictionary and discovered that a ‘fell’ is an animal’s hide or skin with hair, and a fellmonger is somebody who prepares and sells animal skins. It’s either the same as tanning or closely related to it.

I don’t yet know how far back the business goes in Charlton Marshall, but I guess in some form or other it’s been going on since the first herdsmen settled here.

In more recent times, in the 1841 census Charles Dadu(?) aged 24 was a master tanner employing 5 men, and Francis Hopkins aged 61 and his son George aged 22 were both journeyman tanners; William Ball and his son Lewis were also tanners.

The trade can be followed through the census records of the 19th century and various trade directories until we get to the entry of 1880 that first intrigued me, which was ‘Francis Young, fellmonger’. By 1915 this has become ‘Young and Watts Ltd, fellmongers’. The business was carried on in Gravel Lane, and is recalled by the road named Tannery Court at the Blandford end of the village.

Directory entries for Blandford between 1920 and 1939 record Young and Watts at 61 East Street variously as Rope and Twine Merchants, Leather Merchants, and Taxidermists. Perhaps someone can tell me what relation this business had to the one in Charlton Marshall. Also if anyone has any information about the Charlton Marshall business I shall be delighted to receive it.

1881: A fruitful pair

Charlton Marshall. A fruitful pair – During the last year a pair of pigeons belonging to Mrs Easton of this parish have become parents of twelve pairs which they also brought up to maturity. This we think beats anything of the kind previously recorded in our columns.

Blandford Express Jan 22 nd 1881

1881: Merrythought Bone

From the Blandford Express May 21st 1881.

Mysterious Case – Some few days ago as two men were emptying a closet vault at a place called “Burts Close” (which lies between Thornecombe Bottom and Charlton Marshall) they discovered something wrapped in a cloth, which upon examination was declared by them to be the remains of an infant! Information was at once given to the nearest policeman, who, as in duty bound, communicated with his superintendent and the coroner – W. H. Atkinson Esq., who directed him to take possession of the suspected parcel and its contents, and take them to the coroner’s house. This having been done, the remains were shortly afterwards examined by Dr. E. M. Spooner and the coroner in person, who discovered leg and thigh, side and other bones, including a very fine merrythought bone, clearly showing they were the remains of what appeared to be an ancient rooster of the Chochin China, Bramah Pootra, or other large breed. We are informed the coroner declined to put the county to the expense of an inquest, consequently to whom the poor chanticleer belonged, or how he came to his final unsavoury resting place must remain a matter of conjecture. R. I. P.

I have kept the language, punctuation, and spelling as it is in the newspaper. The ‘merrythought bone’ is what we call the ‘wishbone’.

1885: A Conservative Meeting

A well arranged Conservative meeting was held here last Thursday evening in Mr Old’s barn… in conclusion, the Chairman Sir Charles D’Oyly felt it his duty to say a word in behalf of the lord of the manor, Mr Bastard, who in accordance with his well-known impartiality, had kindly offered the use of the Charlton Institute… having been informed that the school-room was not large enough. Mr Bastard, though on the other side, said he made the offer in order do his best to afford a fair hearing on both sides…

Blandford Express October 17 th 1885

1887: Village Pump

The Blandford Weekly News of October 22 nd 1887 reported that ‘On Tuesday last the new pump lately erected by TH Bastard Esq. was formally opened for the public use of the parish.’

Thomas Horlock Bastard was in his 92 nd year, and had invited a few parishioners to meet him at the pump. He pumped some water, drank it, and said it was good and wholesome for the women to make their tea and for other cooking purposes. He went on to say that he had thought of installing a pump for some time and the drought caused by the dry summer had made him put his thoughts into practice. He then commended pure water as preferable to alcohol.

He presented the pump to those present on behalf of the parishioners and said he hoped it would be of good service in the village. The parishioners thanked him and gave three cheers for Mr and Mrs Bastard.

Mr Bastard was Lord of the Manor of Charlton Marshall. He was the great grandson of Thomas Bastard of Blandford whose brothers were responsible for much of the rebuilding in Blandford after the fire of 1731. He seems to have had a keen interest in the provision of clean water because the pump in Blandford Market Square erected by his ancestor after the fire, bears a plaque recording that Thomas Horlock Bastard of Charlton Marshall restored it in 1858, and I’m sure too that I have read that he was responsible for a pump in the Milldown area of Blandford.

Old Ordnance Survey maps show wells in many cottage gardens in Charlton, and I know today that there is at least one cottage that has a trapdoor in the kitchen floor covering the well shaft. The earliest reference I have so far found to mains water is in Kelly’s Directory for 1939 – supplied by the Blandford Water Works Company Ltd. Can anyone confirm when water mains were laid, and does anyone remember the pump in use?

So, next time you walk up The Close, or go to the Post Office, give a thought to that little group standing around the pump in 1887, and perhaps recall too that there are plenty of communities around the world today that would value such a provision.

As a result of this piece, Mr Jim Barfoot has told me that he remembers the water main being laid and before that he remembers residents of the cottages on the main road and others nearby using the pump.

Water came to the village in the 1930s followed by gas and then electricity.

The pump in Blandford used to be in Damory Street near the old grammar school. Our Thomas Horlock Bastard founded the school in 1862 as the Mill Down Endowed School, and in 1864 he had the pump erected for public use on adjoining land. Please does anyone know of a photograph of that pump?

1888: Vandalism

A piece from The Blandford Weekly News June 2 nd 1888.

Charlton Marshall. Garden Robberies. The cottage gardens and allotments in this village have already this season been visited and despoiled of part of the produce by parties who have no right thereto, early plots of cabbage being an especial attraction to these depredators. The well-kept flower beds, abutting the main road, which is an attraction to every passer-by, have also been despoiled by dishonest persons after nightfall. Suspicion rests on certain individuals in the latter matter, and one more spoilation of flowers will be followed by retribution.

1895: Church Restoration

Throughout the summer and autumn of 1895 there was a major refurbishment taking place in Charlton Church and services were held in what we now call the Church Room. Incidentally in the same year Blandford church was also having major changes made.

The architect’s report on Charlton includes the following ‘the structure … is simple, but the fittings are elaborate and magnificent for so small a building. The whole thing is almost unique and so full of interest that the greatest care should be taken to preserve it intact’. The pews were 4’ 7½ inches high (nearly 1.5 metres). The walls were panelled to the same height with finely figured English oak and the pews had doors on them. The wall panelling is still the same height but the present pews were made from the old ones. The interior is still considered magnificent; what a pity it is that at present it cannot be kept open for all to enjoy.

We may smile at the following piece that appeared in the Parish magazine for March 1895.

‘With the growth of devotion amongst Churchmen which has been so marked a feature in the latter half of the present century, the old box pews have almost become extinct in our Parish Churches. Charlton is, we believe, the only church in this neighbourhood, which still retains them, a distinction it is happily soon to lose. The following extract refers to the time when Charlton Church was last restored, and offers a curious explanation as to the reason why pews of the kind now so universally condemned, were first introduced … Bishop Burnett … found that “the gallants would ogle the ladies of the court” “and that these likewise would look about them instead of attending to what Queen Mary called” “his thundering long sermons”. “He persuaded Queen Anne to have all the pews in St James Church raised so high that his captives could see nothing lower than the pulpit, an example which was shortly adopted by many of his dry and long-winded brethren, to the lasting disfigurement of our churches”. We cannot tell whether Dr Sloper shared the sentiments of his contemporary Bishop Burnett of Salisbury … when he constructed the box pews for Charlton Church, but we have every confidence that the removal of these obstructions will be a benefit for which every Church going parishioner of Charlton will be devoutly thankful.’

When the writer referred to ‘this neighbourhood’ I don’t know whether he was being very parochial, or more likely that he didn’t actually know all the churches in the neighbourhood, because as I’ve said before, the little church at Winterborne Tomson, only a few miles away, still has its box pews today, and is unique in so many respects that it’s a ‘must’ for a visit.

1897: Yew Tree

There are lots of yew tees in Charlton Marshall; the biggest and oldest being the one in the north east corner of the church yard. Its girth is about 24 ft (7 metres) and it is certainly older than the church.

It’s a tree that ‘parishioners are, or ought to be proud of’ as the Rector wrote in the parish magazine of September 1897. The next March he had to record that ‘ the grand old Yew Tree in Charlton Church-yard has suffered very seriously from the snow storm which fell so heavily on the night of February 21st. The whole of the North East side of the tree is now practically destroyed and only one of the large limbs … remains’.

1898: Weather

Parish Magazine, 1898. “Tropical England! Ninety-one in the shade. Eight Torrid Weeks! Extraordinary figures! Fires and Drought!” Such was the sensational heading to an article which appeared in one of the London Daily papers on Saturday August 26 th, and we in Dorsetshire, can fully endorse the statements … “The remarkable feature of the 56 days through which we have passed is the persistency of high readings … during the night … average of over 60 degrees, Fahrenhieit … . … in the shade … an average of 79.19 degrees … highest … 92 degrees …”

From the Parish Magazine of December 1908

At Charlton Nov 20th we had the pleasure of listening to a very deep and interesting lecture, which lasted one hour and a half without a check, on Earthquakes and Volcanoes, from the Rev. S.A. Walker, without a doubt it was worthy of any great London Audience. How greatful we should all be to have such an able man amongst us who can expound and explain these great and terrible forces of nature, at the same time we should be very thankful they do not exhibit themselves to any great extent in this country. Motor Cars are bad enough, but burning mountains would be worse. W.J.S.

1910: Church Finances

From the Parish Magazine June 1910

I desire to draw your attention to the state of our Church finances. At Easter there was a deficit of £10.6s on our Church Accounts. … “The collection today is for Church Expenses” are words which do not appeal greatly to our imagination or sentimental feelings … but … we must remember that the services of the church cannot be maintained without expense, and as we have NO PEW RENTS we have to rely entirely on the collections to meet that expense. We are not extravagant in our outside offertories as we only have five during the year…

déjà vu?

1912: Weather

Parish Magazine, 1912. There is little to record this month, the outstanding feature of which has been the unseasonable weather. Not since 1879 have we had such a cold, wet, dismal August. The continual rain has not only spoilt the holidays, but … it has spoilt a great portion of the harvest. This fact has no doubt caused many to doubt the appropriateness of holding Harvest Festivals this year, but we thank God for what we have, not for what we have not, and after all, sad as the loss has been to many employed in agriculture, we have not a famine, so let us thank God for that.

1914: First World War

World War 1 in the villages. Just a little background as we come to the annual Remembrance ceremonies.

Much has been done nationally and locally to commemorate the centenary of WW1. Through books, television programmes, films, and musicals such as War Horse we can have a much better understanding of, and feel for, what was going on. Since I published my book on Charlton Marshall, new online search tools have become available, and locally Blandford U3A has researched the stories of the men on local war memorials; in particular Christine Smith from Charlton Marshall has researched both ours and Spetisbury’s, and Blandford St Mary’s has also been done. Copies of ours and Blandford St Mary’s are deposited in Blandford Museum, Charlton Marshall Parish Council has a copy of ours while Spetisbury’s is on the brink of completion.

Immediately war was declared in August 1914 thirty men from Charlton Marshall and Spetisbury volunteered and within a month almost as many more had joined them. During the course of the conflict at least sixty two men from Charlton Marshall and eighty from Spetisbury either volunteered or were called up; conscription was eventually introduced in January 1916 for single men aged between 18 and 41 – with certain exceptions. Thirteen men from Charlton Marshall and fourteen from Spetisbury are recorded on the war memorials.

We do not know how many families were directly affected in our villages but the impact on communities numbering only a few hundred must have been considerable, especially as those who were absent were among the most active and healthy. Can we imagine the emotions of a young wife who is told a month after the outbreak of war that her husband has died from wounds received in action, only to learn a few weeks later that he is in fact a prisoner of war?

In November 1914 Bertie Martin from Charlton Marshall was home with a bullet wound to the head but the parish magazine reported ‘His trying experience does not seem to have damped his ardour in the least, and he hopes to return to the front shortly.’. He was eventually to lose his life on July 1st 1916 on the first day of the battle of the Somme and is buried in the Serre Road Cemetery in Somme. Bertie was a ‘regular’ having seen 10 years’ service by the outbreak of war, including 6 years in India and Ceylon. Others too who joined up, had seen former service and knew something of military life, but it is doubtful if anything could prepare them for the new mechanised warfare of 1914-18.

In the villages all sorts of fund-raising took place and the women sewed and knitted to provide items for the troops – both those on active service and those repatriated wounded. Some Belgian refugees were housed locally.

Mark Churchill.

Did you make history that day? Can you help?

The last timetabled trains to stop at Charlton Marshall and Spetisbury – Monday September 17th 1956.

The following recollection of Engine Driver Reg Darke is taken from “Life on the Somerset and Dorset Railway” by Alan Hammond, Millstream Books, 1999.

‘One driving memory I can recall was on 17th September 1956. We were working the 4.10pm from Evercreech to Bournemouth … This train was the connection for passengers off the Pines Express for stations to Shillingstone. On this particular evening we stopped at Charlton Marshall Halt and picked up a family of four who alighted at Spetisbury Halt, the next stop along. They then wanted to go over the other side of the platform. The guard had to conduct them across the track. I asked the guard later what they were playing at; he replied that they wanted to take their two young children on the last train. We were the last down train and the 5.18pm was the last up train to stop at the halts. The facts had not sunk in that it was the last official stop at these halts; they were closed that day.’

I would love to know who that family was. Did you make history that day? Does anyone have any idea? If so please contact me. Mark Churchill at mk.cmanor@googlemail.com or 01258 452872.

UPDATE (2023): I have not managed to discover who the family were that travelled from Charlton Marshall to Spetisbury and back on the last day of timetabled passenger services but I have been given more information about the trains that evening from Jonathan Edwards of the Somerset and Dorset Railway Trust (S&DRT).

The train that the family caught was the 5.10pm SO (Saturdays Only) Templecombe to Bournemouth West. On Mondays to Fridays, it ran 25 minutes earlier; its later schedule on Saturdays was due to the fact that the previous train – the ‘Pines Express’ – ran about half an hour later.

The train left Charlton Marshall at 6.01pm, due at Spetisbury at 6.06pm. The Up train was scheduled at 6.07pm, hence the Guard had to quickly shepherd them across the track; this was scheduled at Charlton Marshall at 6.11pm.

These were not the last trains to call at the halts. The last Down train was – potentially – the 6.02pm Bristol Temple Meads – Bournemouth West (7.05pm ex-Bath Green Park), which called to set down only on notice being given to the Guard; it was booked at Blandford Forum at 9.43pm. There was an Up train at 7.19pm at Charlton Marshall (six minutes earlier at Spetisbury); this was the 6.40pm Bournemouth West – Bristol Temple Meads. The Saturdays Only 10.0pm Bournemouth West – Templecombe was booked to call at Charlton Marshall at 10.48pm – this was the last train to call. But clearly the last practical option for a trip to Spetisbury and back was the 6.01pm. This last day of services was Saturday 15th September 1956 (not as I had said, 17th). There was no Sunday service on the Somerset & Dorset. The halts were officially closed on Monday 17th – the date on and from which trains ceased to call. Stourpaine & Durweston and Corfe Mullen Halts also closed on the same day

2005: Tombstones and Memorials

I knew that the White family who lived in Charlton House in the early 19th century had links with Poole and the Newfoundland fishing industry. What I didn’t know was that the Streets who owned it before them, had likewise been in the Newfoundland business. One Saturday morning this summer I went into the church and found Marjorie there talking to two men; one of them was from Newfoundland and was researching the Street family, to whom he was related. He was interested in the big oval monument on the north wall and we then found that some of the table tombs near the door of the church belong to this family too.

The current interest in Family History means that people come looking for tombstones, or in some cases just wanting to see the place where an ancestor lived. The notes that they put in the Church visitors’ book sometimes lead to new information about the village, and sometimes this allows me to give people family links of which they were not aware. My email address is also on a flyer in the church and this has produced some useful contacts.

Charlton House became Clayesmore Preparatory School in 1937, and moved to Iwerne Minster in 1974. We get a significant trickle of former pupils coming through the village, and get such comments in the Church Visitors’ Book as ‘I used to pump the organ here’.

One of the most interesting discoveries was of Henry Mayor who before moving to Blandford in the 1860s, lived in one of the cottages near the church. Again the link came through someone looking for a grave. I subsequently discovered a lot of information in microfilmed copies of the Blandford Express from the 19th century in Poole Local History Centre. There were links with Kingston Lacy, with the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union, with the Temperance movement, and with the chapel in Gravel Lane. The highlight, one summer evening, was to go into Blandford with the person who had made the original contact, and quite ‘by accident’ find Henry Mayor’s workshop; we were just able, in the evening light, to make out his name embossed in the plaster.

Around this time last year, hidden away, I found a beautifully oak-framed Roll of Honour from the first world war; it lists not just those who died, but every man from the village who joined the services – and what a roll call of local names it is. It went on show in the church at the time of the Remembrance Day service last year.

Local people have shared their memories with me, some have loaned me photographs, and some have allowed me to look at old house deeds etc. If you’ve got anything to share, however insignificant it seems, please get in touch; it is probably something that nobody else has mentioned yet. It’s our story of our village.

Charlton Marshall’s War Memorial is located just to the right of the footpath leading to the main door of the church of St Mary the Virgin, which is situated mid-way through the village. The current church cemetery is situated 800 yards along Church Lane, which is on the opposite side of the road to the church. The WW1 Memorial Project produced this document to commemorate those named on the memorial: WWI Memorial Project – Charlton Marshall